The art of diplomacy

An old map of Romania and a fire-damaged print of London: Britain's Head of Soft Power and former Ambassador to Romania speaks with curator Dr Laura Popoviciu about the links between art and diplomacy.

Paul Brummell, Head of Soft Power and External Affairs, FCO

UK diplomats undertake a journey to represent the country’s interests around the globe and works of art from the Government Art Collection undertake a parallel journey. What would you say happens when art meets diplomacy?

Art can offer new perspectives to tackling the major global challenges facing us. Art can also be a powerful element of national identity. There are risks around this, as we have seen when art is used by autocratic rulers to bolster their legitimacy. Art can also be an important element in a country’s soft power – its attractiveness to others. Diplomats aim to support and strengthen the bilateral relationship between the United Kingdom and the host country.

Sir Anthony van Dyck (studio), Katherine, Duchess of Buckingham, with her children, 1633

This is achieved by showcasing British soft power and helping to nurture people-to-people contacts, and also through joint collaboration in tackling the pressing challenges facing the world. Art itself also flourishes where there is a lively international exchange of ideas and people. For example, the development of English portraiture owed much to foreign court painters like Van Dyck.

Art itself also flourishes where there is a lively international exchange of ideas and people.

Engaging with art and culture can change the way people think, feel and behave. In the context of international relations, this is often talked about as ‘Cultural Diplomacy’ and ‘Soft Power’. How do you define these concepts and what is their purpose?

‘Soft power’ is a term coined in 1990 by US academic Joseph Nye, as the ability of a country to secure its objectives through the attractiveness of its culture, values and international behaviour. Nye contrasts this with ‘hard power’, which is about a country’s economic strength and military muscle. He argued that to be internationally successful, a country must deploy both. Since soft power is about attractiveness, it derives from the receiver not the sender. The UK is attractive only when international audiences perceive us to be so.

‘Cultural diplomacy’ is a more focused term, and involves the use by governments of cultural exchange to foster mutual understanding and develop influence. The work of the Government Art Collection is part of the UK’s cultural diplomacy strategy, using the power of artworks displayed in government buildings around the world, which in turn takes its strength from the soft power of British art.

The work of the Government Art Collection is part of the UK’s cultural diplomacy strategy, using the power of artworks displayed in government buildings around the world, which in turn takes its strength from the soft power of British art.

When you were British Ambassador to Bucharest, how did you activate art to influence others in, for example, negotiations that took place in the Residence?

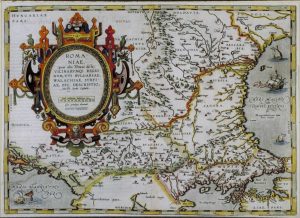

Abraham Ortelius, Map of Romania, 1584

The artwork which generated the most attention from Romanian guests was Abraham Ortelius’s 1584, Map of Romania. This sparked many conversations about the origins of modern Romania and the country’s changing historical fortunes. It also served as a sign of the Embassy’s interest in Romania’s history and culture, and as mark of respect for the host country.

We decided to name the three official guest bedrooms in the Residence after three remarkable women who played important roles in the development of the UK-Romania relationship: Queen Marie of Romania (1875-1938), a grand-daughter of Queen Victoria; English-born Maria Rosetti (1827-1876), wife of the literary and political princely leader Constantin Alexandru Rosetti; and Elsie Inglis (1864-1917), the founder of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, who played a crucial role in caring for injured service personnel on the Romanian front in the First World War. Each bedroom was decorated with a painting or a photograph of its namesake. I think our guests welcomed our celebration of the deep historical connections between the two countries.

Were there works at the Residence in Bucharest that visitors might have been surprised to find in a diplomatic building?

Carel Weight, Life in Putney, 1956

Perhaps the most surprising item on the Residence walls was a fire-damaged London print. We had retained it as a reminder of the damage sustained to the previous Residence building during the Romanian Revolution in 1989. My personal favourite among the Collection artworks on display in Bucharest was Carel Weight’s Life in Putney, one of several pieces to enliven my office wall. It was a placid autumnal suburban scene, with the height of action represented by a couple walking their dog. I never did identify a Romanian connection to the painting, though.

In a blog post you wrote in 2018, you concluded that the ‘Government Art Collection plays an important part in the mobilisation of British soft power to support the development of our international friendships’. Looking ahead to the future of the UK’s foreign diplomatic relations, are there any ways you think the Collection could make new contributions to soft power?

I think one area which could be developed more strongly is around enhancing awareness in the UK of the Collection and its role. To this end, the Collection’s forthcoming move, with the prospect of accessible display space at the new site, is I think an opportunity to showcase material which illuminates the role of the collection in support of diplomacy. Another important development is around technology, and the opportunities the digital revolution has created to make art from the Collection available to a wider audience than those who will physically visit an embassy or ambassadorial residence.

What is the Government Art Collection?

Why does the Government have an art collection? What does it collect? Why is the Collection spread across the world?

A working collection

Works from the Collection are regularly on the move. Find out what’s needed to make this happen and the job mission of the artworks themselves