Behind the Image: Impromptu Photo-Booths and a Studio on the Go

Keeping the image bank up to date is critical for the Collection. With short windows for photography between conservation and shipping, and awkward spaces to photograph in when we audit works on site, the Collection needs a responsive photographer.

Meet Tony Harris, our Digital Media and Photography Manager, who tells us about documenting the Collection on camera and keeping the pictures up to date.

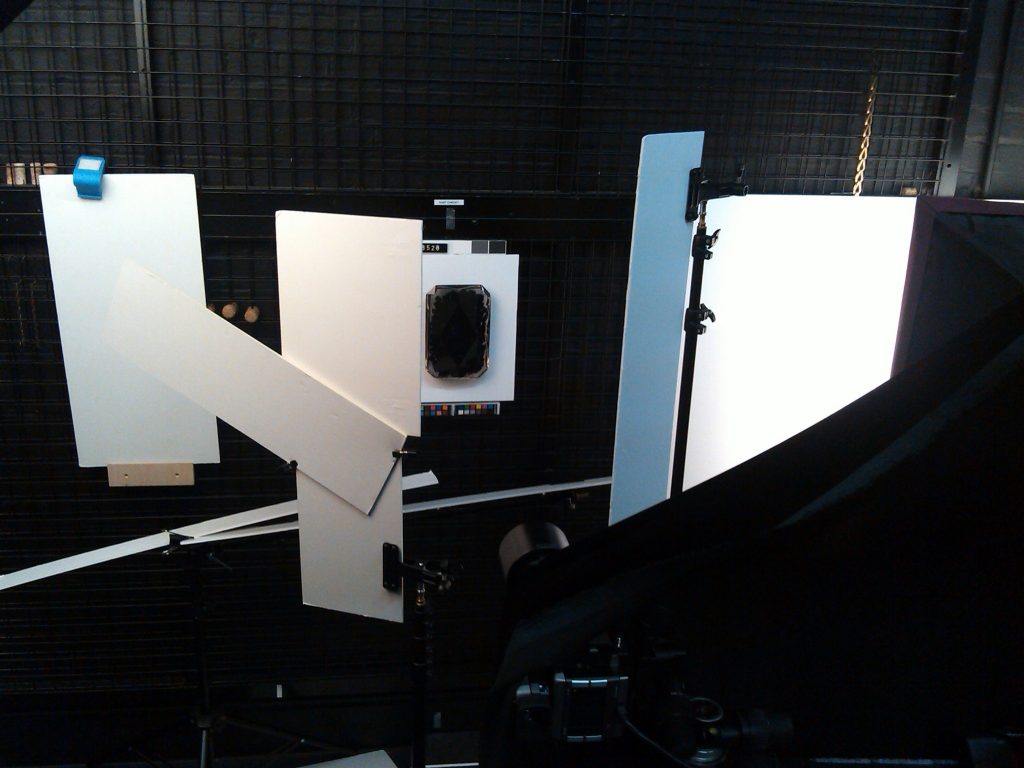

Tony’s set-up for the photography of Lucy Skaer’s Me VIII (2012)

A particular sort of image

‘Photographing an artwork for collection documentation purposes is a bit different to photographing it for a book, or for publicity. Our objective is clarity rather than aesthetic appeal and the challenge is to bring out the best aspects of the object. The lighting needs to enhance rather than detract from the object. It needs to look like a museum photograph and this means keeping to a series of standards.’

Up to scratch in three dimensions

‘I am also Secretary to the UK Museums Photography Standards Group, which keeps up to speed with best practice in the industry, and helps people adopt the established standards. There is an international standard (ISO) for two-dimensional cultural heritage photography, which was published in 2017 and which the Collection complies with but there isn’t one for three-dimensional objects yet.

Lucy Skaer, Me VIII (2012)

With three-dimensional art objects like Lucy Skaer’s Me VIII (2012) shown here, you need to make sure that the sharpness is constant. It’s not an easy task with a three-dimensional artwork like this, and differently-angled surfaces.

We have a photography studio at the Collection and we use a high quality, medium-format digital camera, high quality lighting (including flash lighting), and quality control devices – such as colour target charts. These let you apply colour correction without human intervention. Once the photograph has been taken, you need to run it through colour management software on a computer to undertake all the necessary quality checks.’

Chasing the shot

‘Works from the Collection seem to be constantly on the move, the objects aren’t on site all the time and getting good, accurate, photography of the work is important for inventory purposes. A photograph will be needed whenever an artwork leaves the building to record the latest state of the object – and we’re constantly lending! We often just have a small window of opportunity to photograph objects following any conservation. I have often had to set up an impromptu photography booth on location, most recently the case when auditing the works on loan to the British Embassy in Gibraltar.’

What happens to these photographs?

Once taken, Tony’s digital photographs are stored on the Cloud, where we also have digitally-scanned copies of our historic film archive 35mm transparency (i.e. slides), as well as 5×4 transparencies, 5×4 black-and-white negatives. The photographs in our image catalogue are used on our website, as well as for publicity purposes, or in our interpretation materials – where Collection curators explain more about the art. They might also end up in a publication, or even in your home as a print-out. Ultimately, as Tony remarks, ‘the photographs inject a further narrative – it’s about making our Collection accessible’.

Edited by Dr Claire FitzGerald, Curator (Modern and Contemporary)