Windrush Day: art, archives and emotional legacy

Windrush Day 2023 marks 75 years since the arrival of the HMT Empire Windrush at Tilbury Docks, Essex on 22 June 1948. On board was one of the first large groups of post-war Caribbean immigrants to the United Kingdom. This pivotal moment in history has undeniably influenced knowledge, culture and industry across all levels of British society, explains Curator Shasti Lowton.

For communities that have been marginalised throughout history, the act of being seen, remembered and preserved is a form of activism. By collecting and increasing accessibility to stories of the Caribbean community in Britain, grassroots organisations have filled in the historical gaps and voices missing from mainstream archives. Some community archives (such as the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton and the George Padmore Institute in Finsbury Park) have been able to establish themselves as official organisations with the goal of recording and documenting historical facts for future generations.

Artist archives often contain secondary material and paraphernalia that can document inspiration, process, creative thinking and various key moments in an artist’s career. Both artist and community archives, along with oral and ritual tradition, exist to transfer information and sustain memory, regardless of whether that memory is collective or individual. The multifaceted nature of archives has seen them become a useful tool for artists to inspire, research and document their work. Whether it is a mainstream, community or specific artist’s archive, at some point in their career most artists will integrate this resource into their practice.

Andrew Jackson, Pouyatt Street, outside where Amy once lived, Kingston, Jamaica, 2017 © Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson, Hand #1, Kingston, Jamaica, 2017 © Andrew Jackson

So if the role of the archive is to record and preserve the facts of a moment, what is the role of an artwork? While an archival object can elicit an emotional response it can’t capture an emotion in the same way that an artwork can. This allows art the potential to archive a feeling of a particular memory rather than the facts of it. So, whilst the factual legacy of the Windrush generation is still in the process of being recorded in archives across the UK, it is artists from the Caribbean and its diaspora that are working to capture the often complex feelings of what it means to be part of the Caribbean community living in Britain today.

Collectively the works below demonstrate the important role that artists can play in communicating and preserving emotions and feelings pertaining to a moment in time. While the factual information collected by archives are key to helping future generations understand the timelines of historical events like the arrival of the Windrush, it is clear that works of art (particularly works by artists from marginalised communities) are essential in helping us understand how these events made us feel.

Andrew Jackson

The pull to return to one’s ancestral home or region is particularly strong for descendants of migrant communities who have established bases in the UK. In 2017, artist Andrew Jackson visited Jamaica, meeting relatives and family friends for the first time. The trip allowed him a firsthand insight into his parents’ experiences, enabling him to understand his own heritage more fully.

It also gave him the opportunity to revisit the stories and reminiscences he had heard as a child growing up in the UK. In the photograph Pouyatt Street, outside where Amy once lived, Kingston, Jamaica Jackson photographs the street where his mother Amy Jackson once lived in Kingston. In the centre of the image stands the lone figure of a young girl dressed in a loose fitting t-shirt and denim shorts. Her back is facing the camera, which seems to have captured her mid-movement, giving the viewer the impression that she is unsure of whether she wants to journey forward. The shade from the overhead vegetation simultaneously covers her and emphasises the sunlit street ahead, perhaps a metaphor for the bright future in front of her. The composition and subdued tones of the work concurrently convey ideas of home, hope, loneliness, determination and the anticipation of a journey. All thoughts that may have crossed the artist’s mother’s mind when considering whether to undertake her journey to the UK.

Hurvin Anderson

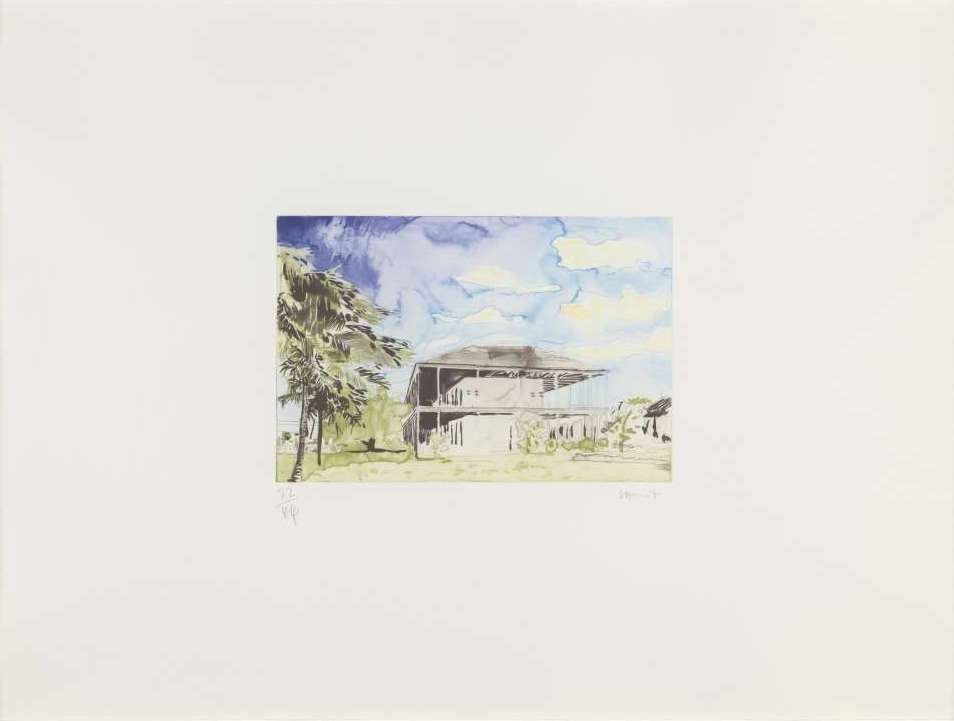

Hurvin Anderson, Untitled, Nine Etchings, 2005 © Hurvin Anderson. All rights reserved, DACS 2023.

Hurvin Anderson’s Nine Etchings portfolio was inspired from a residency that the artist undertook in 2002 at Caribbean Contemporary Arts in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. Four etchings in this portfolio depict uninhabited beach houses amid palm trees and tropical foliage. The remaining five show semi-figurative and abstract ‘snapshots’ of architectural details – lines of a brick wall and criss-crossed patterns of fences.

His depiction of barriers in these prints subtly alludes to the country’s post-colonial identity, creating visual contrasts to the notions of leisure and relaxation now associated with these places. By choosing to record fragments of the architecture in this way, Anderson suggests a feeling of unease and detachment from wealthy tourists who have made the island their seasonal playground. While tourism is the main economic driver of the Caribbean (contributing to a third of the GDP for most countries in the region), climate change impacts and the rising costs associated with it make it bittersweet for local communities.

Rita Keegan

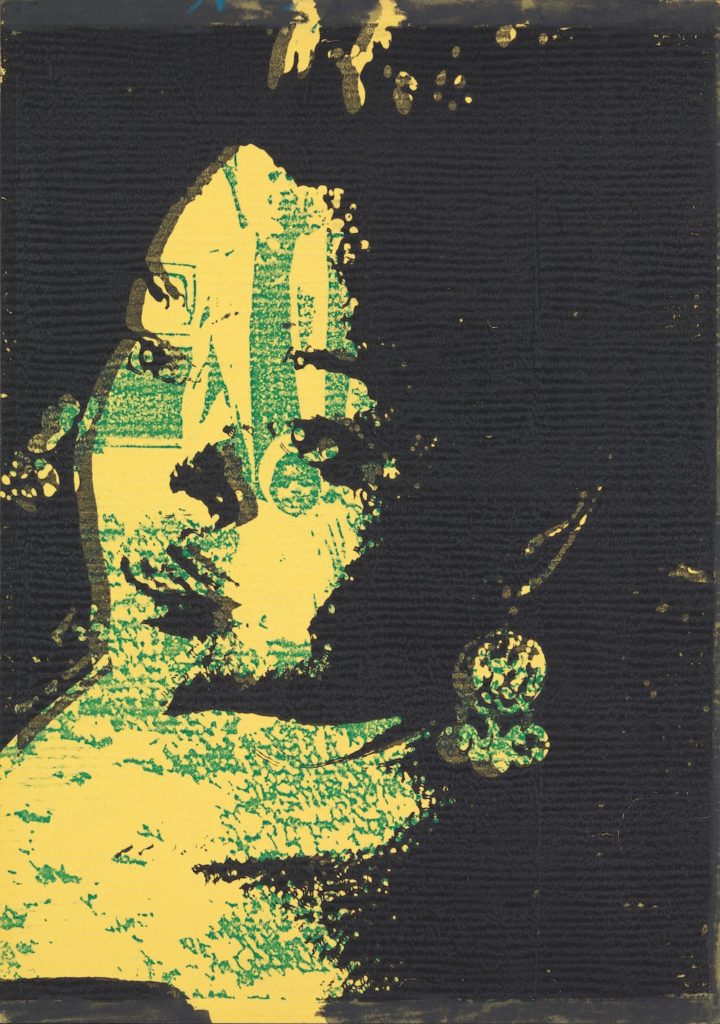

Rita Keegan, Mother and Me, 2023 © Rita Keegan

Rita Keegan positions herself as both an artist and archivist. Her copy art collages overlay images from different sources and operate as a metaphor for Keegan’s exploration of her own layered identity that incorporates Caribbean, Canadian, American and European influences.

Keegan began to experiment with this medium in the 1980s, when she was a member of the co-operative print shop community Copy Art. Using the photocopier as an affordable and accessible artistic tool, Keegan was drawn to its manipulative powers and ability to imbue images with new life. The works are monoprints on sugar paper, fed through a photocopier multiple times to layer different images and colours.

Uniquely, Keegan holds a collection of original family photographs that date back to the 1880s. These personal moments of familial history often feature in Keegan’s collages. They poignantly honour her ancestors whilst expressing feelings of love, acceptance, community, happiness and belonging.

Sonia Boyce

Sonia Boyce, Devotional, 1994-2004 © Sonia Boyce. All rights reserved. DACS 2023.

Devotional and Devotional II by Sonia Boyce serve as both artwork and archive. The names and dates in this piece were collated by Boyce over years of conversations with people about their favourite Black female singers. Spanning from the pre-1960s to the noughties, they range from the jazz singer Elizabeth Welch, to Sade and Ms Dynamite.

Listing the singers vertically, Boyce creates a colourful totem-like object that presents a distinct history of popular music. The interaction with other people in creating her work is a key part of Boyce’s artistic process, who views her works as collaborations.

Of all art forms, music is perhaps the most powerful in being able to transport you to a moment in time or elicit an emotional reaction. It is impossible to read one of the familiar names in Boyce’s Devotional works without remembering the music they created. With Devotional, Boyce monumentalises not only the named Black female singers but also the collective memory of how the music they produced makes us feel.