Rita Keegan: ‘We humans have a desire to collect’

Rita Keegan talks about her childhood, her start as an artist and how her identity has shaped the art she creates.

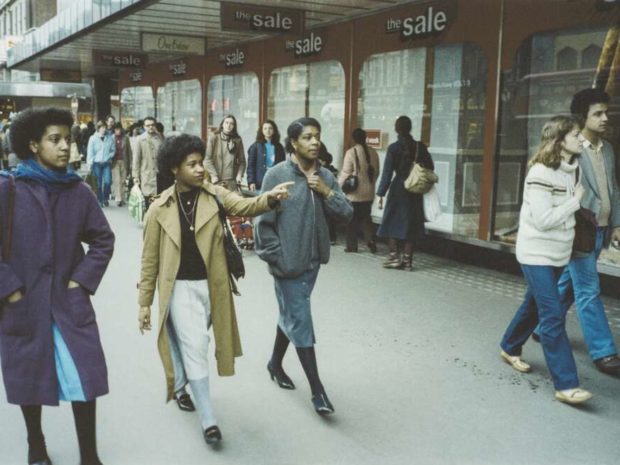

An artist whose work recently became part of the Government Art Collection, Rita Keegan is a key but overlooked figure in the history of Black British art. Born in New York, of Caribbean and Canadian descent, she migrated to the UK in 1980.

Keegan helped establish the Brixton Art Gallery where she curated the first exhibition by the Black Women Artists collective. She also co-founded CopyArt, a resource for community groups and artists working with computers, scanners and photocopiers.

In this interview, the artist talks about her childhood, her start as an artist and how her identity has shaped the art she creates. Read the full transcript below.

Transcript:

I’ve always drawn, I’m a maker. As a little girl if you asked me what I wanted to be, I wanted to be an artist.

I don’t think I realised the ramifications of that but that’s what I wanted to be and so I’ve been focused on that in a sort of non-focused way. It is just what I am.

I went to an art High School in New York called Art and Design and we were taught advertising we were taught fashion so I learned how to do cut and paste which is basically, get your scissors and collage and I used to make paper dolls as a little girl and so cutting and colour and paper were were quite natural and maybe that comes from having a textile background too. And I was not not allowed to do that and the art teachers, didn’t you know, one told me I might I was just crazy enough to make it. Which I figured was a compliment.

I was never afraid to work with new media. And when I came here I was involved with Brixton Art Gallery. Through them I met people who were starting to set up this photocopy organisation called CopyArt. You used the photocopier to teach people how to do flyers and posters but also a lot of artists were doing work with using the photocopier.

I was very keen on owning what I produced because there was a lot of discussion about the ownership of of the body and also the ownership of of images so gender and race would come into it.

I was incredibly lucky to have a photographic family resource that goes back to 1880 and you know, why wouldn’t I use it, my assumption was that everybody had these family photographs. Little did I know that I was incredibly lucky. I also felt it was important to represent people of colour, not just working in the fields, because we did lots of other things and we dressed up, you know. So to be able to use these images that I didn’t have to appropriate, they were my family.

We humans have a desire to collect, you know. Sometimes we collect on purpose, sometimes it just sticks with us. Collections are markers. I have pieces and things that I don’t know why [they] never left me.

There’s the identity that you have and there’s also the identity that is forced on you and then there’s the identity of society and how you negotiate your way through that. Growing up in the 50s and 60s, there’s a consciousness – especially in America – of race so you know, so already I’m aware of gender and already I’m aware of race, so those become part of your perceived identity. Then there’s your identity if you are a foreigner, I never thought of myself as an American until I came here and people would give me, would attack me for American foreign policy and like I had control of American foreign policy. Yes, I’m American but my father was from Canada, my mother was from the Caribbean, I was born in the Bronx, you know what do you own and where do you own? I’m a New Yorker, I’m also a Londoner, those identities mix very easily. Knowing who you are but also being able to understand the fluidness of who you are is quite important to be able to stand up for who you are. You know if you know where you’ve been then you can go through where you’re going.

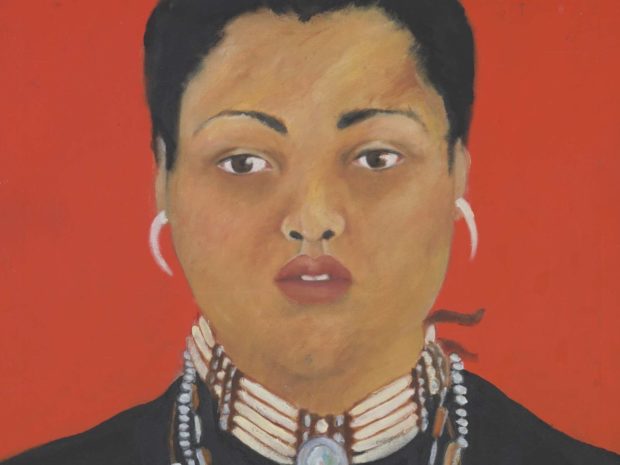

It’s very hard to know that you’re worthy in a society that doesn’t reflect your worthiness. I don’t even know if she [Rita as a little girl] would believe me when I would say that your work is going to be in national collections. I mean, why would I think that? You know, as I wandered through the Metropolitan as a child and I’d see you know, darker faces and they would be maids and slaves and stuff and I would marvel at the quality of the work but these would be nameless women. And the fact that that my work is not a nameless woman is incredibly important. And it’s big it’s very big because we haven’t been, we have been a possession and an add-on, we haven’t been the subject and it’s nice to be the subject of my story.

Because I would like people who make change actually make change and that looking at diversity does not mean that you disregard who they are but you acknowledge who I am.