A Life Livelier: British art and diplomacy in Costa Rica

23 artworks from the Collection hang on the walls of the British Ambassador’s Residence in San José. From historical prints to modern and contemporary art, the new display gives us an insight into the cultural and diplomatic connections between the UK and Costa Rica.

A postcard from Costa Rica

Anglo-Costa Rican diplomatic relations officially began in 1848 while Frederick Chatfield, a diplomat in the Foreign Office, was based in Guatemala. In 1849, Chatfield signed a treaty of friendship, cooperation and navigation with Costa Rica, after Costa Rica formally declared its independence from the United Provinces of Central America. Diplomacy between the two countries soon intensified, and the British presence in the region became much better documented.

On 5 August 1851, Chatfield wrote to foreign secretary Lord Palmerston that there were 163 British residents in the five Central American states. Most of them, he explained, were located in Costa Rica and Guatemala and included a number of ‘engineers, carpenters, miners, hotel keepers, clerks, coffee planters, an estate manager, a gardener, a teacher, a mule driver, a cochineal (a type of insect that produces natural dye) grower, a student, a boatbuilder, a butcher, a doctor, a blacksmith, and a land surveyor’.

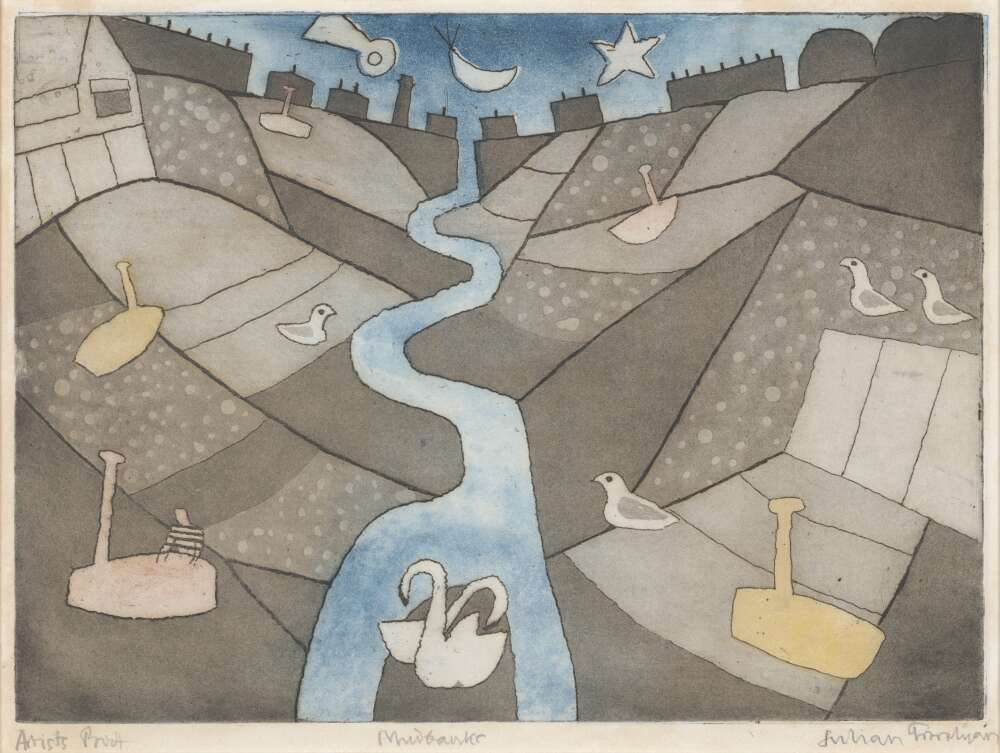

Julian Trevelyan, Mudbanks, 1978 © Courtesy of the artist’s estate / Bridgeman Images

The British landscapes on display at the Residence are a reminder of that first documented British presence in Costa Rica. For instance, Julian Trevelyan’s Mudbanks show the artist’s fascination with the River Thames. He wrote:

Here on the muddy banks of the Thames in Chiswick I put down my tap-root; my life was measured by its tides, and my dreams were peopled with its swans and seagulls.

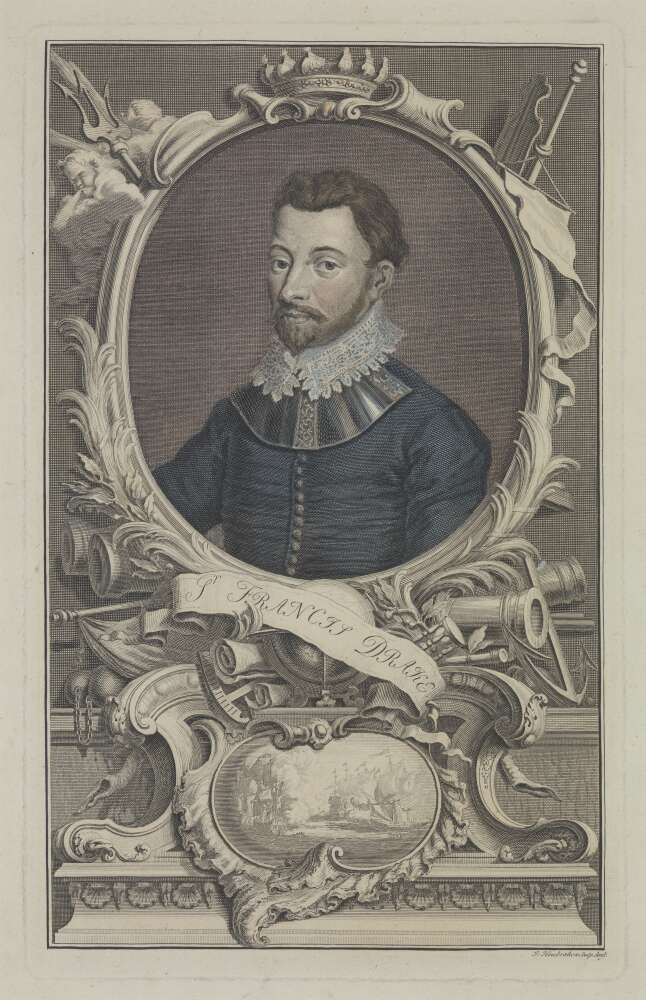

The Dragon from Bahía Drake

While official diplomatic relations began in the 19th century, interactions between the two countries date back much further, to the 16th century and to one of Britain’s most well-known historical figures. Sir Francis Drake, one of Queen Elizabeth I’s most famous sailors, voyaged the world between 1577 to 1580. He used a small bay in Costa Rica as a port during his raids on Spanish and Portuguese ships carrying treasure from their colonies in South America. This earned him the nickname El Draque or The Dragon. Rumour has it that Drake’s treasure is still buried in this small bay, now known as Bahía Drake.

The Tree of Life

James Ireland, Untitled © James Ireland

Almost 6% of the world’s species live in Costa Rica. The country is a leader in conservation and a key advocate for fighting global climate change. In the Ambassador’s Residence, waterfalls, volcanic landforms, meandering paths and hills encourage visitors to wander between real and symbolic landscapes from both the UK and Costa Rica.

Ian Fleming’s linocut Thistles in the Sun reminds us of rural Scottish landscapes. James Ireland’s etching of a tree begins to shed its leaves at the turn of the season, deconstructing those idyllic English landscapes found in holiday brochures and advertisements.

On the other hand, Carmen Gracia’s tree of life is a motif found in many ancient cultures. As a symbol, it unites heaven and earth, connecting all forms of creation. In the Residence, the print also references Costa Rica’s giant ancestral trees, which are found throughout its tropical forests.

Treasures of the natural world

There are over 28,000 species of orchids worldwide. 52 of these can be found in the UK and over 1,400 in Costa Rica. One of these, the ‘Guaria morada’ or ‘Guarianthe skinneri’ is the nation’s national flower.

Margret Kroch-Frishman’s vase of red and yellow orchids makes us consider how countries can connect through what they have in common, opening up debates about current issues such as the care and preservation of the environment.

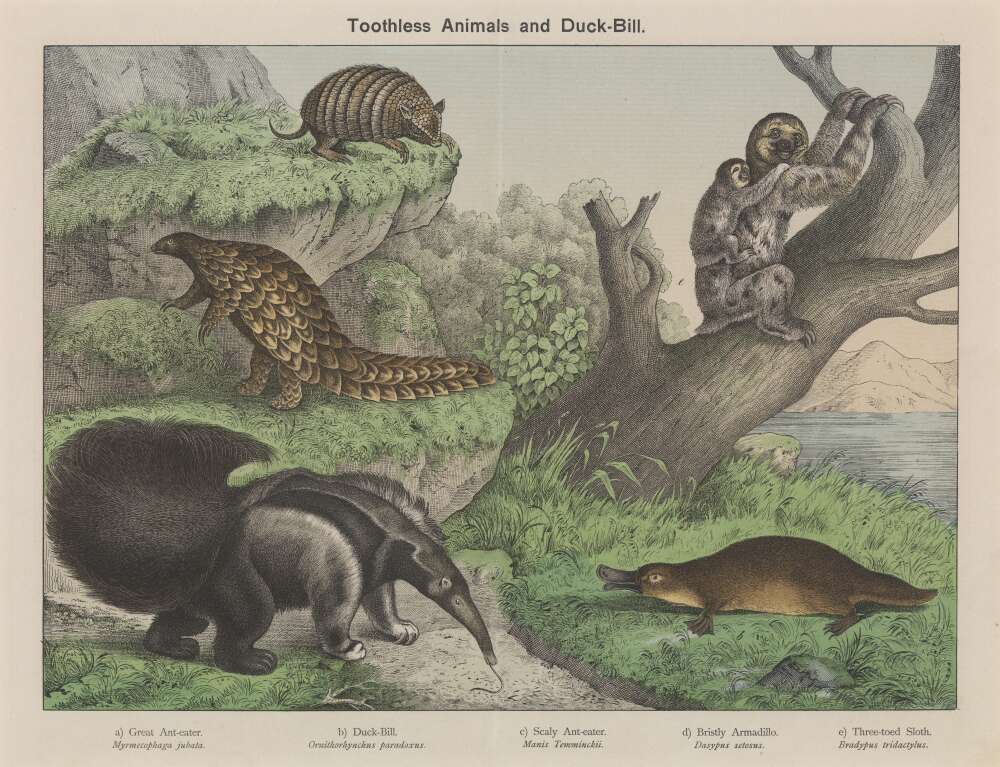

Unknown, British 19th century, Toothless Animals and Duck-Bill, from the Natural History of the Animal Kingdom for the Use of Young People: Part I, 1889

In this printed illustration from a 19th century publication titled Natural History of the Animal Kingdom for the Use of Young People is another of Costa Rica’s national symbols: the sloth. Synonymous with the country’s reputation as a treasure of the natural world, the sloth’s endearing appearance and peaceful demeanour remind us of our collective responsibility towards these vulnerable creatures and of the need to protect them for future generations.

A Life Livelier

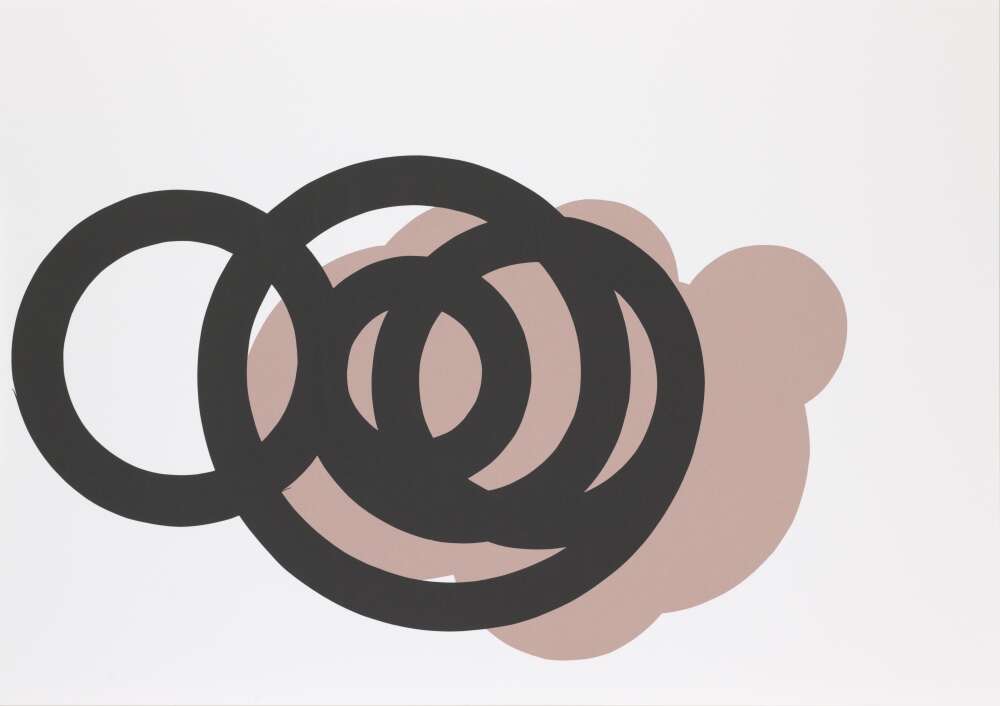

Claire Barclay, A Life Livelier 6, 2009 © Claire Barclay

Claire Barclay’s screen prints (from the series A Life Livelier) are a celebration of bold sculptural forms and bright colours and bring a more forward-looking dimension to the display. The familiar shapes – discs, circles, bowls and cups – are simple but ambiguous in their meaning. Barclay is interested in how contemporary craft fits in a culture defined by mass production. She is fascinated by the contradiction of the commercial world’s desire to make money out of objects such as dream catchers and crystals, all of which were designed initially to encourage people to reject mass-production.