The Adventures of a Time-Traveller: Researching the Historical Collection

Dr Laura-Maria Popoviciu in conversation with Dr Claire FitzGerald.

CF: If you had to describe your role as curator at the Government Art Collection in five words – what would these be?

LP: Stimulating, enriching, surprising, enjoyable, meticulous

CF: What, in your opinion, is distinctive about the historical artworks in the Collection?

LP: What fascinates me about these historical works is that they inspire me to look beyond the first layer of paint; to cut through blurred lines, to find a reflection that is deeper and truthful to the original intention of the artist. Once untangled, the stories behind these works, that sometimes go back 400 years, act like compasses, helping us to position ourselves and better understand our relationship with the world.

The words of the French novelist Mathias Enard come to mind, in an interview in Dilema Veche (No. 823, November-December 2019):

in a postcolonial and decolonised world, we struggle to untangle complicated cultural connections and globalisation; we do not know whether the image we project is one that others conform to, or instead, that of two mirrors facing each other; the alterity or an amalgam of all the images, stories and visions of others.

Philip Alexius de László, Madame Tibor de Scitovszky, 1927 © Crown Copyright, UK

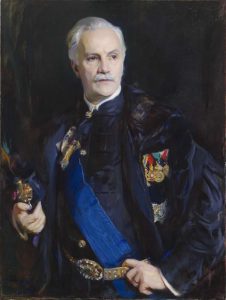

Philip Alexius de László, Tibor de Scitovszky, 1927 © Crown Copyright, UK

Finding the perfect place to display Collection works also invites a multifaceted approach: a curious mind, research and serious reflection. Embassies are spaces of intersection, of different influences that facilitate both unexpected and staged encounters. Once installed, the works both enliven these spaces and continue to develop themselves. The most recent example of such a spectacular occurrence was an installation in the British Residence in Budapest of two newly acquired paintings by Philip de Laszlo. They show the owners of an elegant villa in neo-baroque style in the hills of Buda in Hungary in the early 1930s.

Today, this elegant building is the British Ambassador’s Residence in Budapest and the two paintings, reinstated after an absence of 73 years, echo the original display. Their presence in the Residence prolongs our contact with a particular atmosphere and with the characters of a world that is no longer tangible.

CF: Working as a curator involves a lot of communication, both within our organisation as well as outside it. We exchange ideas and thoughts with professionals from the arts sector, with members of the general public, and also with high-level politicians. Would you like to share an encounter that has stuck with you?

LP: In October 2018, I had the pleasure of meeting the British Ambassador to Turkey, Sir Dominick Chilcott. He had also served as the British Ambassador to Iran during the attack on the British Embassy in 2011. I asked him if he was willing to recount his experience for the podcast I was making, A Meeting of Cultures, to which he immediately responded with generosity.

We then parted, though not before sharing a few thoughts about my home country, Romania, which he had visited on a cold winter’s day in the 1990s. A few months later, as I sat in the recording studio with my radio producer, waiting for Sir Dominick to join us on Skype from Ankara, I was part of one of the most magical hours of conversation. I had asked him a question inspired by a quote from Andrew Solomon’s 2016 book How Travel can Change the World:

As a diplomat, you represent Her Majesty the Queen and the UK Government in the country to which you are appointed. Travel is part of your career. Solomon wrote: ‘You never see yourself more clearly than when immersed in an entirely foreign place.’

I asked him to what extent he resonated with these words and the dialogue we subsequently had opened up a range of captivating subjects touching on theology, philosophy and British diplomacy. It then drifted towards aspects of the history of the interwar period, American cinematography and Iranian culture, and ended on a contemplative note with memories of travel and lost opportunities. This encounter has stuck with me because of how naturally it unfolded, and has reminded me of how precious it is to exchange ideas about our humanity, and to explore them with grace, profoundness, elegance and genuine curiosity.

CF: Do you have a favourite historic work, and if so, why this one?

LP: With every work of art that I research, my universe of images becomes richer. I continuously add to this receptacle of knowledge, cementing it with depictions that intrigue me through their puzzling iconography, complex provenance, authorship and compelling stories. Each of them becomes ‘my favourite’ as I begin to unravel their mystery.

In 1959, the Collection acquired a painting showing King William III as Solomon. A rather faint signature placed at the bottom left of the painting identified the artist: Jan van Orley, a 17th century painter and prolific tapestry designer from Brussels. A stencil on the stretcher suggested that this work featured in a Christie’s sale on 10 April 1953, with a different attribution.

I first had the opportunity to examine this three metre-high painting in November 2015, when it returned to the Collection from Hampton Court Palace, where it had been on loan for 25 years. Its viewing prompted me to address a number of questions in an attempt to shed more light on this painting and the context of its making: where did the idea of depicting William III in the guise of the biblical king Solomon come from? Could the king’s attendants be identified? When was this work painted and where was it originally displayed? How frequent were visual and textual references relating to Solomon during the reign of William III?

Jan van Orley, King William III (1650-1702) Reigned 1688-1702, as Solomon, 17th century © Crown Copyright, UK

Interviewed by Dr Claire FitzGerald, Curator (Modern and Contemporary)