Art questions with… Christopher Samuel

We sat down with artist Christopher Samuel to discuss art and access for Disability History Month.

Artist Christopher Samuel.

How did you become an artist?

I stumbled into art. After spending a long time in hospital in my 20s, I was unsure where I fit in in the world. Eventually, I enrolled on an art and design course. Secretly I’ve always enjoyed art, but felt that it wasn’t for me, or for people like me. It did not feel accessible.

During the course, I did everything I could to avoid drawing; I thought I would be disappointed, because of how my condition affects my hands. It wasn’t until my lecturer told me I had to create an ‘alternative self portrait’ that I tried. This was the same week that I got my first electric wheelchair which had a big square armrest. I picked up a biro pen, I used the armrest to support both hands holding the pen and I drew myself.

It was a life-changing moment. The drawing looked like me. In that moment, my whole perception of art and my sense of worth and purpose changed, something I’d been searching for for years.

What are the main themes of your art?

I make work about disability and identity politics, often echoing my own lived experience. I work in lots of different mediums – from illustrations and installation, to print and video – in a way where I can take agency over the disabled or marginalised experience.

I use redaction a lot in my work – the idea of revealing and concealing things by removing or blocking out certain information, to suggest a different narrative. I also use humour and poetic subversiveness to make work that is accessible to everyone.

I want to make work which opens up a dialogue about a lived experience which many people may not directly identify with.

How does your disability inform how you create art?

When I first started to make art, I had a serious internal conflict about not being pigeon-holed as a ‘disabled artist who makes work about disability’. Like lots of disabled people of my generation and culture, I was brought up to think ‘disabled people shouldn’t complain’. And for a long time, I didn’t want to be identified as disabled. But I think it is important to make work about my real experiences and the politics around that because this is my lived experience. And the lived experiences of other disabled people too.

Our stories are underrepresented – historically and culturally – and that needs to change.

Do you have a piece of work that you feel is significant or important to you as an artist?

Three pieces of work stand out to me as really important because they tackle issues that have affected disabled people over the century and continue to be contentious – care, access, agency and inclusion.

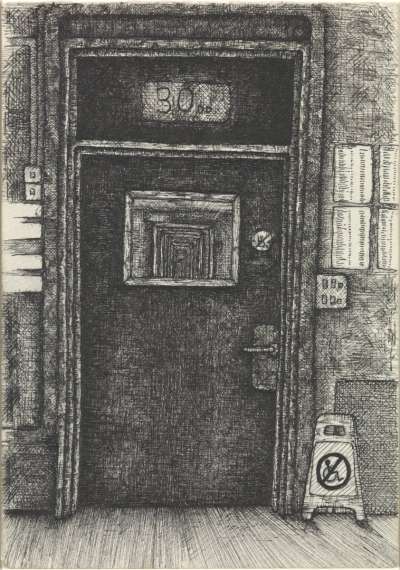

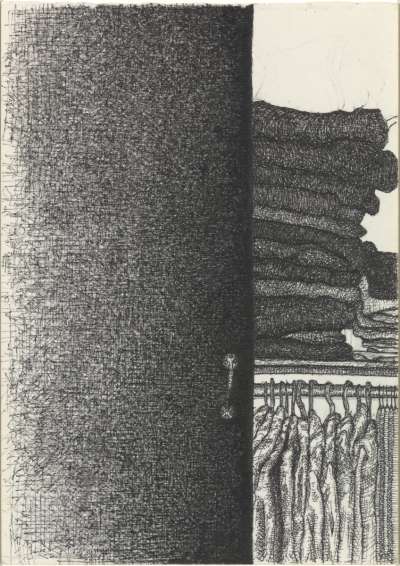

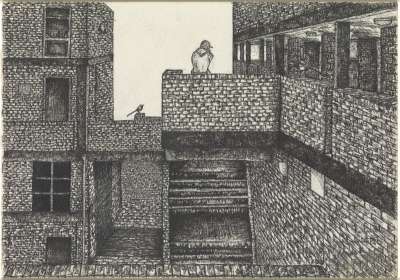

The Welcome Inn (2019) was my first big commission where I redesigned a hotel room at Art B&B Blackpool to create a sleep-in installation that people can spend a night in. I designed the room to be inaccessible to able-bodied people, to allow them to experience a space that is not designed for them, and to challenge the culture of ‘one size fits all’ architecture.

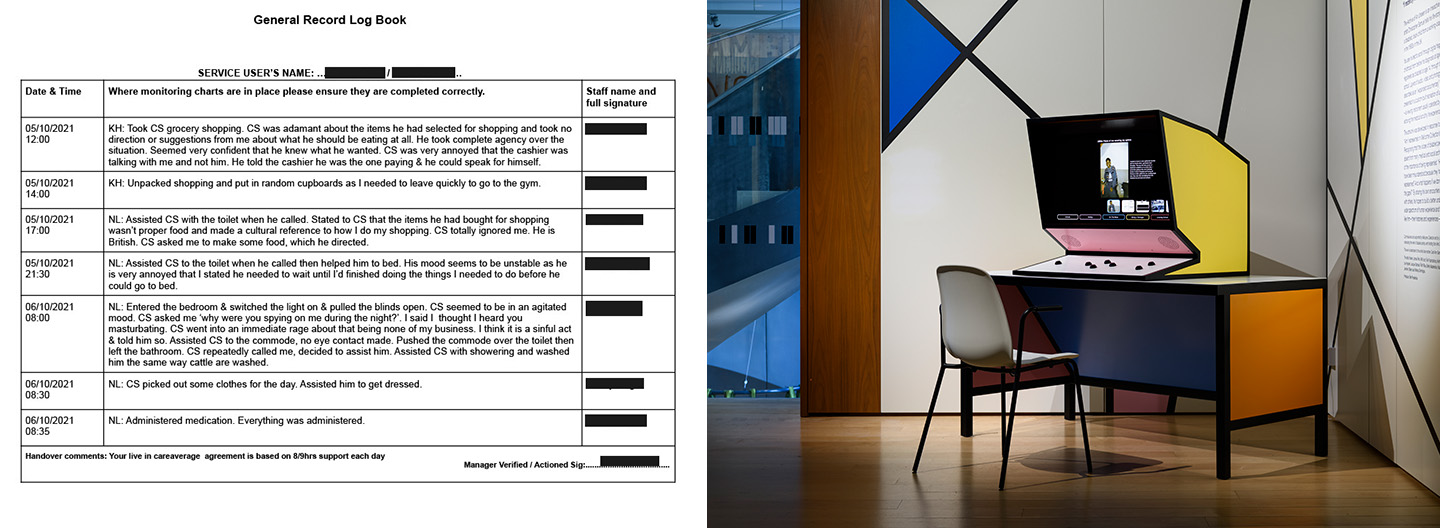

The Cared For Network (2021) is a digital artwork that takes the form of a carer’s logbook – a document which records what daily care is given by a carer to a cared for person, for the care company to track – and subverts it to reflect the cared for person’s experience instead. It explores the power dynamics at play in a prescribed care relationship.

The Archive of an Unseen (2022) is an interactive sculptural installation on display at the Wellcome Collection. It is a custom built Microform reader, which visitors can explore the contents of. Inside, it tells the story of me growing up as a Black, disabled, working class boy in the 80s and 90s in London. It aims to address some of the imbalances of representation that currently exist in medical and social archives.

Christopher Samuel, The Cared For Network, 2021, Careful Networks Online and The Archive of the Unseen, 2022. Commissioned by Unlimited and Wellcome Collection. © Christopher Samuel

What are you most proud of in your artistic career?

I think it might be my Mum seeing me at my first exhibition, shortly after I’d graduated. It opened the same night, and in the same gallery, as an exhibition by Yinka Shonibare, who is someone who I definitely look up to as an artist.

I’d just finished university, and I’d just successfully won the right to live independently – and not in a care home – which that body of work (Housing Crisis, 2018) was about. My mum had watched me trying to get through university and then fighting when I was made homeless. I think this was the moment where I could see my Mum’s pride in me, that her son had achieved the things that many said he couldn’t.

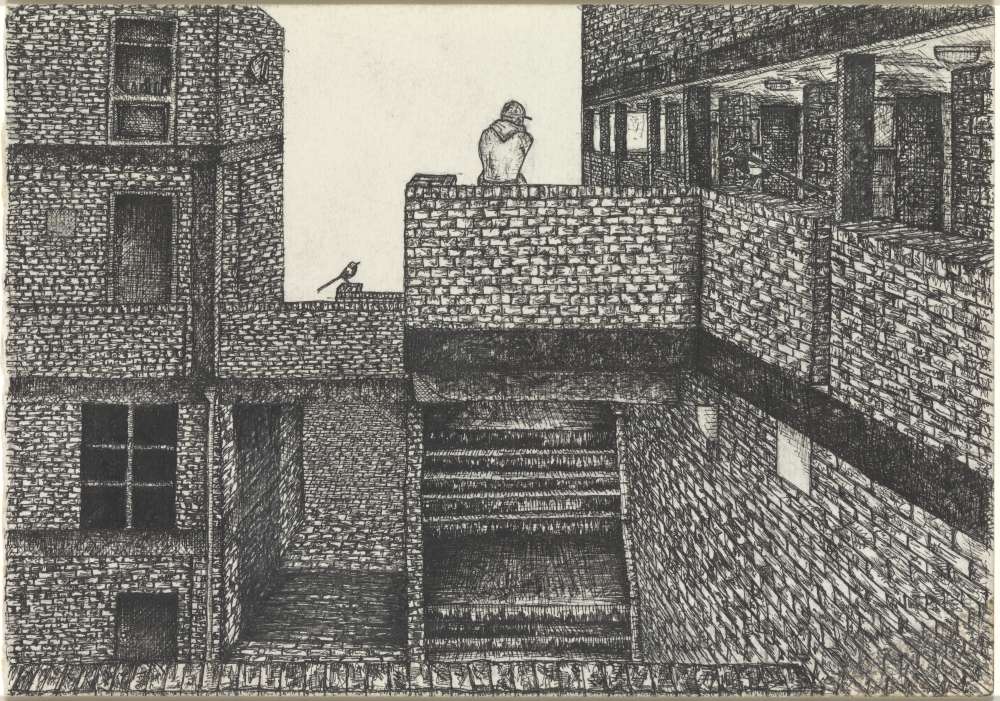

Christopher Samuel, Estate Portrait, 2018 © Christopher Samuel

What motivates you to make art?

The ability to have a voice. For a long time, I was not in control of lots of aspects of my life, and did not feel I had a voice (or was heard). Art allows me to speak for myself and for other people who are voiceless, and to speak about issues which affect the lives of the voiceless and that are unjust. I also love the process of research – investigating, interrogating and understanding why and how my experience is the way it is, and how other people perceive me or the disabled community.

What do you think the role of art in society should be?

Art can allow people to think about things in a different way, or to invoke thoughts and ideas which can have a positive influence. I don’t expect everyone to have the same experience of my art, but that is the beautiful thing about it – it gives a space for others to engage with ideas and experiences in their own way.

Good art has the power to change people.

In your opinion, what can the arts and culture sector do to better support artists that identify as disabled?

Working as a disabled artist can be a bit of a minefield – juggling benefits, working hours and practices, access support, managing your own health, travel… Some organisations are leading the field in considering access, equal opportunities and representation, while others seem to be playing catch-up.

I work with a team of people that assist me with producing work and running my practice, day to day. My practice increasingly involves working collaboratively, especially as my projects get more ambitious. As someone who can’t work for long hours, it has been a challenge to work out how to navigate the sector to allow me to successfully make work and build a career, while also managing my condition.

The most important thing I think is to ask questions – and not to be afraid to ask ‘what do you need to make this work for you?’

Christopher Samuel’s The Archive of the Unseen can be seen at the Wellcome Collection from 12 December. Find out more about his practice on his website and follow him on Instagram.

This interview was conducted in collaboration with The Disability Unit.