Body, mind and soul: the making of Lord Byron

Lord Byron was a great curator of his image. On the bicentennial of Greece’s 1821 Revolution and War of Independence, discover Lord Byron through works of art and letters from the Government Art Collection and Newstead Abbey.

‘The best of him at his best time of life’

In 1814, Thomas Phillips exhibited seven paintings at the Royal Academy summer exhibition. Among these, observed the critic William Hazlitt, were two portraits displayed in the Great Hall that seemed ‘to be of the same individual’. One was titled simply Portrait of a nobleman and the other, Portrait of a nobleman in the dress of an Albanian.

6th Lord Byron, Thomas Phillips, 1813, NA 532. Courtesy of Newstead Abbey, Nottingham City Museums and Galleries.

When Lord Byron sat for Phillips for both these portraits in 1813, he was 25 years old, in the first flush of fame and all the trappings that came with it. He had published the first canto of his Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage the year before, with all copies selling out in three days and leading him to exclaim ‘I awoke and found myself famous’. Both images were carefully staged and even altered at the sitter’s request – one to reinforce his position among his fellow writers and to perpetuate the Byronic hero myth, the other to champion the Greek cause. In 1823, he actively participated in the Greek War of independence and his death during the campaign gained him the status of national hero in Greece.

While the ‘cloak portrait’ was copied numerous times, with one version offered to his publisher John Murray for display and promotion at his publishing house in Albemarle Street, the equally spectacular portrait in which Byron wears a costume he bought in Epirus was concealed temporarily and locked up in a case by his new owner and mother in law, Lady Judith Noel in order to protect his daughter, Ada, from her father’s questionable reputation.

Thomas Phillips, George Gordon Noel Byron, 1813

But how did Byron manage to generate such a powerful image? The public persona he presented was constructed through fashionable clothes, hairstyle and studied gestures as well as through dieting and concealment of his physical disability: he was diagnosed with a club foot. When ‘impertinent persons’ complimented his ‘robust appearance’, he suffered deeply as his ideal was to be ‘pale and interesting’. In 1814, the year his public image attracted so much attention, Byron also became the first man in Britain to receive the visit of the inventor of phrenology, the German physician Johann Gaspar Spurzheim. The latter believed that the shape of human temples affected poetic creativity. After assessing the shape of Byron’s head, he concluded that his ‘good and evil were at perpetual war’. Despite his anxieties, Byron succeeded in perpetuating an image that conformed to how he wished to be perceived: with ‘gentle manners’, ‘pale, marble temples’, ‘handsome countenance’ and ‘fine blue veins’.

‘An Old, Old monastery once’

View of Newstead, John Bell of York, 1866, NA 243. Courtesy of Newstead Abbey, Nottingham City Museums and Galleries.

The association with Lord Byron has cemented Newstead Abbey in the popular imagination across the world. Byron, however, was not the first creative mind to be inspired by this beautiful landscape. Newstead has been an inspiration for artists and writers ever since the house was built in the 12th century.

John Bell’s View of Newstead was painted in 1866, 42 years after Byron’s death. The canvas is huge, measuring over 3 x 2 metres, and hangs on Newstead’s north staircase. This view differs from most of Newstead, in that it is taken from far back on the west side of the upper lake, and includes no people.

This view comes closest to capturing the incredible sense of place that Byron described so vividly in his writing – this majestic gothic ruin, central to an atmosphere of ruined, desolate isolation. The small boat on the lake is a reference to Byron’s great uncle William, the 5th Lord Byron. William held mock naval battles here with his personal fleet of ships and live cannon. One of his gothic cannon forts is just visible on the western shore, nearly engulfed by the wild forest.

Cornelius Varley, Newstead Abbey, 1825

While Newstead’s mystique was the perfect backdrop for staging lively entertainment, it also inspired spectacular optic experiments such as Cornelius Varley’s view. A watercolourist and an optical instrument maker, Varley was the inventor of the graphic telescope. A variation of the camera lucida, this scientific instrument enabled Varley and his fellow artists to not only draw an object by tracing it, but also to translate the image seen through the eyepiece into line, tone and colour. Patented in 1811 and specifically intended to support artists to record the world as accurately as possible, Varley’s exquisite invention received great acclaim at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Varley visited Newstead in September 1824, five months after Byron’s death, making precise drawings of the Abbey’s ruined arch. No doubt, his optical device enabled him to create a painting that appears to be the visual equivalent to Byron’s description of the place from his poem Don Juan: ‘before the mansion lay a lucid lake, broad as transparent, deep and freshly fed by a river’. Varley’s painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy annual exhibition of 1825 with the long title Newstead Abbey, Nottinghamshire, formerly the residence of the late Lord Byron, taken from the garden, showing his dog’s tomb, and the Annesley Diadem, now the seat of Col. Wildman. It was the new owner who invited Byron’s daughter and great mathematician Ada Lovelace, to visit Newstead to embrace her father’s legacy.

With its many layers, Newstead Abbey was, just like Varley’s all-absorbing and translucent lake, a vivid reflection of Byron’s poetic, inventive and eccentric mind.

‘A Stamp of Immortality’

Newstead Abbey was a powerful muse for Byron’s soul too. He saw his beloved home as a metaphor for his family heritage, and its influence, on the direction of his life.

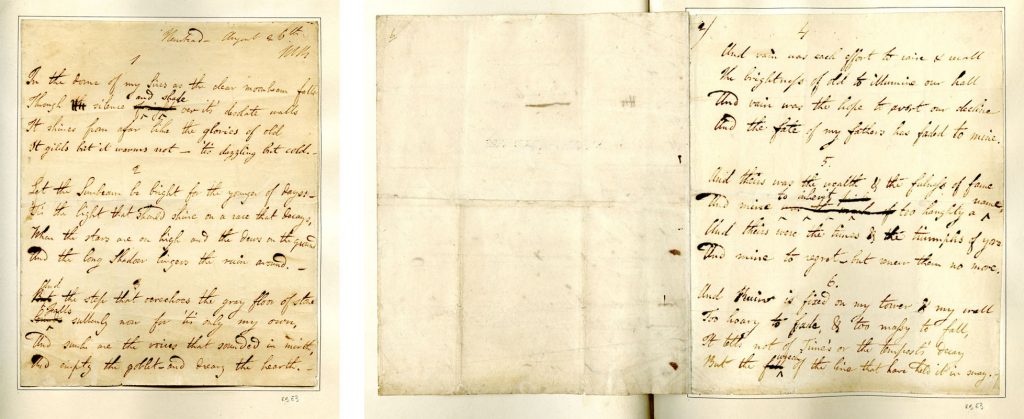

Byron wrote the manuscript poem In the dome of my Sires at Newstead in August 1811, two months after his return from two years of travelling across Europe. He had returned to England to a litany of awful news. His school friends Hargreaves Hanson and John Wigfield had both died. His former lover John Edleston had also been lost to a fever – the need to keep his homosexual relationships secret only heightening Byron’s grief.

Manuscript: In the dome of my sires, Lord Byron, Newstead Abbey, 26.8.1811, RB E3. Courtesy of Newstead Abbey, Nottingham City Museums and Galleries.

More potent than any of these losses was that of his mother, Catherine Gordon Byron. She had died at Newstead, two days before her son’s return from Europe. A grief stricken Byron could not bring himself to attend her funeral, instead sparring with his servant Robert Rushton at Newstead.

Byron wrote his moving poem in the following days. Here, he compares Newstead’s physical manifestation of his ancestry with the life that he saw collapsing around him: ‘It tells not of Time’s or the tempest’s decay, But the wreck of the line that have held it in sway’. The poem remained unpublished until 1878, over 50 years after his own death.

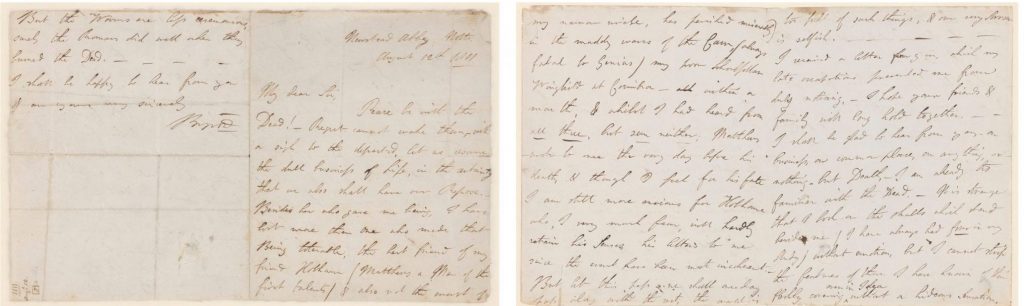

Letter written by Lord Byron to Robert Charles Dallas, from Newstead Abbey, 12 August 1811

‘Besides her who gave me being, I have lost more than one who made that Being tolerable, the best friend of my friend Hobhouse’. At the same time he wrote the poem, a desperate Byron also sent a letter to his distant cousin and literary agent, Robert Charles Dallas, lamenting the death by drowning of Charles Skinner Matthews. A close friend from his university days at Cambridge, Matthews was also a regular visitor at Newstead. On his first visit, Skinner recalled an unexpected ritual: ‘I must not omit the custom of handing round, after dinner, on the removal of the cloth, a human skull filled with burgundy’. Found by a gardener in the grounds of the decommissioned abbey, the skull, which Byron had assumed it once belonged to a monk, was repurposed and turned into a goblet. Typical of his era, Byron’s morbid fascination led him to compose a poem written from the perspective of the skull as a memento mori. His letter to Dallas is a meditation on the fragility of life, an attempt to romanticise death by contemplating the four skulls that he had in his study as well as an aspiration to immortality. As Percy Shelley noted, Byron was, after all, ‘The Pilgrim of Eternity’.

Written by Simon Brown, Curator at Newstead Abbey and Dr Laura-Maria Popoviciu, Pre-1900 Curator, Government Art Collection