‘The unseen worlds around us’: the legacy of Ada Lovelace

‘Enchantress of Number’, a compulsive gambler, 'princess of parallelograms', the world’s first computer programmer, a graphic novel character, a pioneer of AI. These are some of the ways Ada Lovelace has lived in our collective imagination. Her inquisitive, scientific mind and visionary ideas continue to resonate today and inspire technological advancements. For the anniversary of her birth on 10 December, curator Laura Popoviciu explores some of the unexpected connections between Ada Lovelace’s scientific observations and a work of art by Goshka Macuga in the Collection.

Margaret Sarah Carpenter, Ada Lovelace (1815-1852), 1836

Intersecting threads

In 1843, the photographer Antoine Claudet took one of only two surviving daguerreotypes (an early type of photograph) of Ada Lovelace. Against a hazy landscape background, 28 year-old Ada is dressed in black, with a typical Victorian bun and her hands clasped together. This pensive figure with ‘young blue eyes’ (as her father, Lord Byron, remembered her in Childe Harolde’s Pilgrimage) made one of the greatest contributions to the development of modern Western science.

In the same year that the photograph was taken, Ada translated Luigi Menabrea’s French description of Charles Babbage’s invention, the Analytical Engine, into English. She added her own extensive footnotes and described how Babbage’s device would function like a weaving loom invented in 1801. Joseph Marie Jacquard’s silk weaving machine could automatically create images using a chain of punched cards; Babbage’s system could weave algebraic patterns in the same way.

Seeing the potential of this invention (maybe even more than Babbage had) Ada made the crucial observation that instructions and data that were fed through punch cards could represent not just numbers, but letters, images and musical notes too. This turned out to be the foundation for the first computer program.

Intersecting worlds

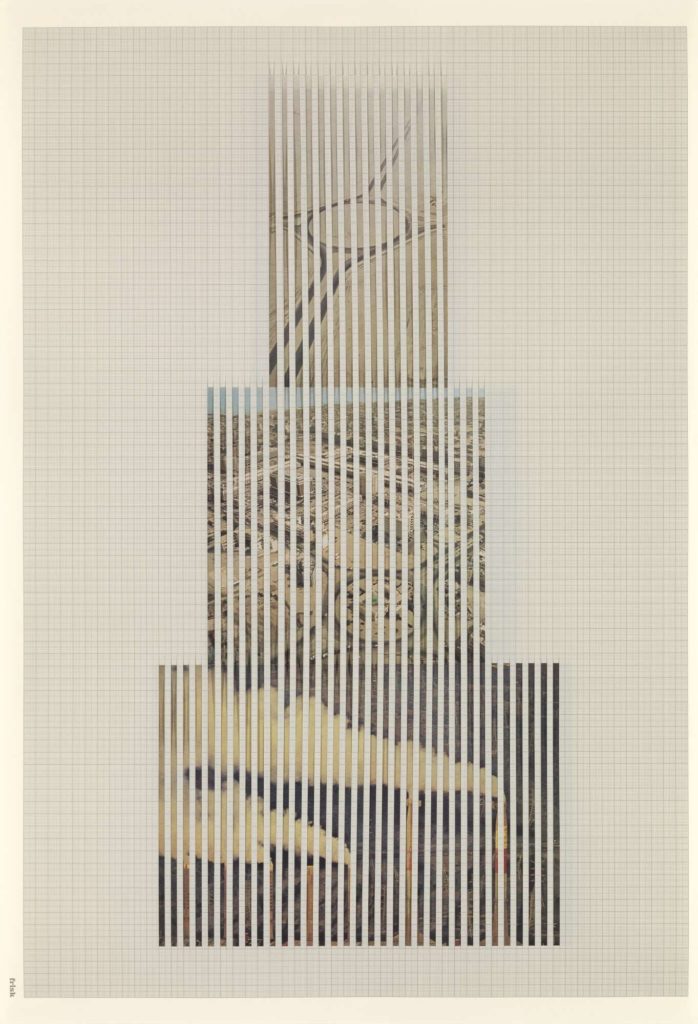

Inspired by Ada’s thinking, artist Goshka Macuga created a series of collages in 2019 which weave together past, present and future. Each collage includes archival photographs; onto those, Goshka superimposed patterns that look like punch cards and looms used for weaving a Jacquard tapestry – similar to those used by Ada when she gave instructions for the Analytical Engine. The artist invites us to see through and beyond the surface – opening up mini universes which tell stories about everything from the evolution of mankind, to technological advances. Each image is filtered through the repetitive grid, encouraging the viewers to reposition themselves and see the bigger picture.

Goshka Macuga, Discrete Model 021, 2019 © Goshka Macuga. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023.

Climate and photography

Discrete Model 021 brings together three archival photographs from National Geographic magazines. The top image shows a highway and roundabout under construction in Kuwait in 1969. The original image in the magazine is accompanied by a short text on the ‘power of oil, which sends the society down the path of progress’.

The middle section shows an aerial view of the Al Murqab area of Kuwait also taken in 1969. Notice the contrasts between the old bazaars and the new concrete and glass buildings, and how the Abdullah Al Mubarak Mosque rises from the traffic circle.

The bottom image, on the other hand, is a 1973 record of a power plant in New Johnsonville, Tennessee. This coal plant generated electricity between 1951 and 2017 but was destroyed in 2021 as it failed to comply with the Clean Air Act.

By bringing together these three images and presenting them in these visual sequences, the artist makes a powerful statement about the ecological crisis as a result of human intervention. Her looms can be understood as prompting us to pause and reflect on the future of the planet as well as calling us to action.

As far back as 1848, Ada made similar observations about the environment and used photography to illustrate her ideas. She expressed these in the form of footnotes to an article titled On Climate in Connection with Husbandry which was written by her husband, William King and published in the Journal of the Royal Agricultural Studies. Ada saw the potential of photography and its contribution to advancing science and human knowledge. She also endorsed the use of photography for constructing meteorological instruments for the observation of climate and crops.

Endless imagination

Imagination is the Discovering Faculty, pre-eminently. It is that which penetrates into the unseen worlds around us, the worlds of Science. — Ada Lovelace

Goshka Macuga’s collages also encourage us to use our own imagination to make new connections and to weave our own patterns of interpretation into them. ‘The choice of reference material’, she has said, ‘is subjective and designed to trigger an individual interpretation rather than projecting a concrete message’. Macuga’s liberating recommendation could even encourage us to reassess Ada’s legacy today: ‘discrete’ like a footnote, but powerful enough to connect the ‘unseen worlds around us’ and render them visible in ways that only Ada Lovelace could have imagined.

Behind the scenes

Want to learn more about the portrait of Ada Lovelace in the Government Art Collection? Watch this behind-the-scenes video of the mathematician’s portrait as part of a new display dedicated to technological transformations in the National Portrait Gallery, in London.

With thanks to artist Goshka Macuga and Josephine Breese at Kate MacGarry Gallery.